In addition to the red and orange garnets described in previous blog articles, the green minerals or varieties of this extensive mineral group are particularly important in the gem and jewellery trade.

Specifically, the garnet minerals grossular and andradite, i.e., calcium-aluminium and calcium-iron garnets, respectively, represent three important gemstones: Mali garnet, tsavolite, and demantoid. These are found in very attractive green colours and enjoy great popularity, especially in combination with the pronounced vividness and brilliancy resulting from their high refractive indices.

Mali garnet

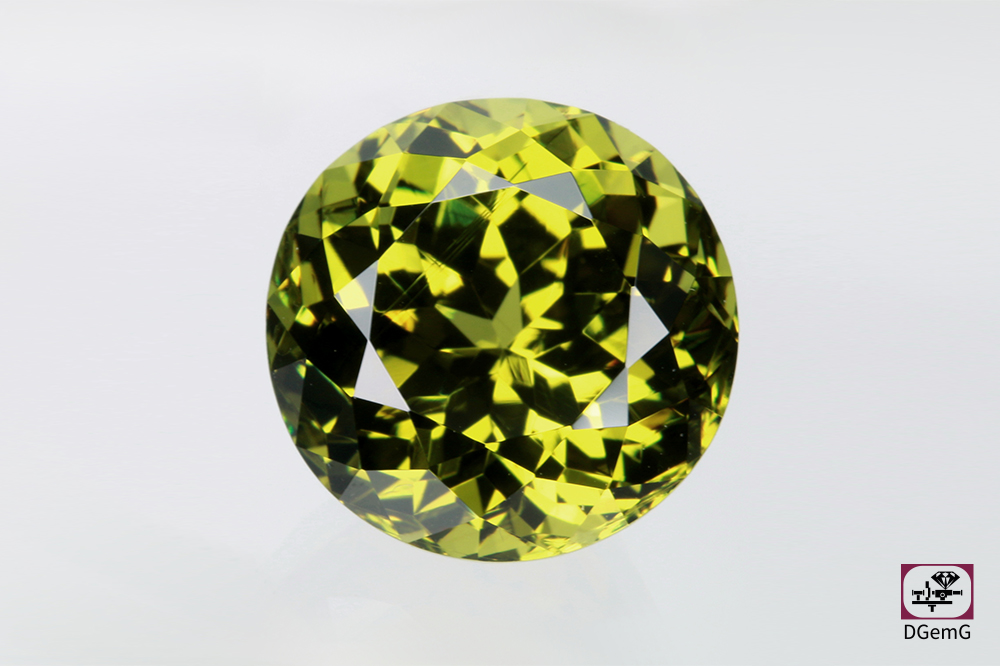

A Mali garnet from the collection of DGemG. 6.07 ct, Photo: T. Stephan

A Mali garnet from the collection of DGemG. 6.07 ct, Photo: T. Stephan

A relatively new gemstone of the garnet group was discovered in 1994 in the West African country Mali. These are iron-coloured mixed crystals of grossular and andradite, mostly yellowish-green or greenish-brown in colour. A speciality are the chromium-coloured green grossulars from the Kayes deposits, known commercially as chrome grossular. In terms of colour, they can be very similar to tsavolites from East Africa. The rough crystals from Mali can reach sizes of more than 10 cm, bur are then largely opaque. Large crystals specimens, for example, over 60 cm in size, are noteworthy. Such large crystals are used for engraved objects. Cut transparent stones usually weigh between 1-2 ct; larger stones are often rich in inclusions.

Tsavolite

Tsavolites from the collection of DGemG. 1.53-2.12 ct, Photo: DGemG

Tsavolites from the collection of DGemG. 1.53-2.12 ct, Photo: DGemG

The emerald-green variety of grossular was discovered in Tanzania in 1967 by the Scottish geologist Campbell Bridges, who operated a mine near the town of Komolo, which was later taken over by the state. Bridges then systematically continued his sear and discovered in 1970 deposits in Kenya, close to the Tsavo National Park, where he then operated the famous Scorpion Mine until his violent death in a robbery in 2009. Afterwards, the mine was abandoned and reopened in 2015.

As with the blue zoisite, also discovered in Tanzania a few years earlier and subsequently named tanzanite, a name was sought for the newly discovered green garnet. Here too, it was Henry B. Platt of the New York company Tiffany, who, in 1973, suggested the name tsavorite or tsavolite. While in America the name tsavorite was prevailed, after the place of discovery Tsavo and the ending “ite” often used for minerals, the term tsavolite is used in most German-speaking countries, also after the place of discovery Tsavo and the Greek word lithos for stone. Both names are accepted by the CIBJO.

Trivalent vanadium is responsible for the emerald green colour of tsavolites, which distinguishes them grom green, chromium-coloured grossulars (so-called chrome grossulars).

Since their discovery, a few exceptionally large tsavolite crystals have been found in both Tanzania and Kenya. The largest transparent tsavolite rough stone found to date came from the tanzanite mine in the Merelani Hills of Tanzania and weighed 185 g (925 ct). This was cut to produce the world’s largest clean tsavolite to date, weighing 325.13 ct and measuring 42.11x36.46x28.34 mm. The value of the cut stone is estimated at approximately US$ 2 million. A second spectacular cut tsavolite is the 116.76 ct “Lion of Merelani”, which was faceted from a 283 ct rough stone and is housed in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington. The stone was also discovered near Merelani, Tanzania, in 2017.

In general, the tsavolite crystals mined in Tanzania and Kenya are relatively small, and cut stones of more than 2 ct are rare.

Demantoid

A demantoid garnet from the collection of DGemG with spectacular "horse-tail“. 2.82 ct, Photo: T. Stephan

A demantoid garnet from the collection of DGemG with spectacular "horse-tail“. 2.82 ct, Photo: T. Stephan

In 1853, children discovered green pebbles in the Bobrovka River in the Urals. Initially, they were thought to be chrysotile, i.e., olivine or peridot, and were called “Ural chrysolite” or “Siberian chrysolite”. Gold and gem prospectors made further discoveries in rivers north and later south of Yekaterinburg, and the primary deposits were finally discovered at the end of the 19th century.

When cut, the mostly small stones developed a strikingly fiery appearance and, due to their attractive colour, became very popular at the Tsar’s court and in the jewellery stores of Moscow and St. Petersburg, also known as “Bobrowsk Emerald” or “Ural Emerald”.

The actual identity of the stones as garnets was established by the Finnish mineralogist Nils Gustaf Nordenskiöld in 1864. He identified the green crystals as chromium-coloured andradites and suggested the name demantoid, meaning “diamond-like”, based on their exceptionally strong brilliancy and dispersion. The name was officially adopted by the Russion Mineralogical Society in 1871. In 1887, demantoid was introduced as a new gemstone at the Ural Industrial Exhibition in Yekaterinburg.

Demantoid enjoyed particular popularity in Russia between 1875 and 1920. Examples include various pieces of jewellery from the workshop of the famous Russian court jeweller Peter Carl Fabergé. During this period, demantoids were also exported to Europe and America and were incorporated into jewellery by renowned jewellers due to their exceptional attractiveness – emerald green colour, high brilliancy and high dispersion.

After the Russian Revolution, the demantoid market was politically depressed for a long time, making this high-quality gemstone virtually unsuitable for jewellery production due to its limited availability. It wasn’t until the 1990ties, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and discoveries in other countries, especially in Namibia in 1996, that demantoid began to experience renewed demand.

Demantoid crystals are generally small, and specimens weighing more than 10 ct are very rare. The largest demantoid ever found comes from the Urals and weighs 252.5 ct.

When cut, stones above 1 ct are already very rare and can fetch prices of several thousand euros per carat. A special characteristic of demantoid garnets are the so-called “horse-tail” inclusions, fibrous inclusions that resemble a horse’s tail. The exact origin and composition of these inclusions are still debated. The mineral chrysotile has been described in Russian demantoids, but recent studies show that they could also be hollow channels. The “horse-tails” are often considered a characteristic of Russian origin, but similar inclusions can also be found in demantoid from other occurrences. Many customers prefer a stone with “horse-tails” to one without inclusions, as long as the inclusions do not significantly impair the brilliancy.

Jewellery pieces with exceptional demantoids find their way into auction houses and achieve high sales prices. Examples include a ring from 1895-1900 featuring a 7-carat demantoid and diamonds, which sold for US$ 101,500 ad Christie’s, and a ring featuring a 6.47-carat demantoid and diamonds, which sold for US$ 89,375 at Sotheby’s.

Authors

Dr. Ulrich Henn, Dr. Tom Stephan & Dr. Thomas Lind, DGemG

© 2025